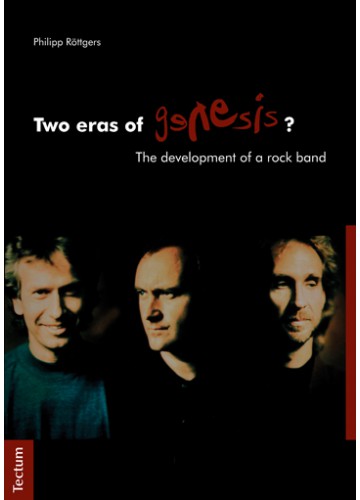

Genesis is one of the most successful British rock bands, hands down. And a band with a long and diverse career that was able to allow all its members to have also long and diverse solo careers (and in some cases very successful, too). Genesis always seemed to have an invisible touch on their listeners and fans. Starting off as a progressive rock band in the early 1970s with singer Peter Gabriel and his strange costumes and masks, the band changed into a pop band with single hits in the 1980s after he left and drummer Phil Collins took over the microphone. At least that is the common conception. Philipp Röttgers takes a look beyond and asks if this change even exists or if there is some kind of misunderstanding. He turns it on again and analyzes certain songs from both “eras”, takes a look at live performances, music videos, album covers and press and fan reviews. He runs through the band’s history and also includes the solo careers to find out if their image should be renewed.

Two eras of Genesis? The development of a rock band on Amazon: Two eras of Genesis?: The development of a rock band

Philipp Röttgers has written a book about Genesis, various reviews and essays, interviewed band members and was consulted as a Genesis expert by various magazines and journals like the The National Post (one of Canada’s largest daily newspapers), General-Anzeiger Bonn, IKZ, Westfälische Rundschau and more.

You can find Philipp’s Genesis website here:

The Rock Band “Genesis” From a Scholarly Perspective

Philipp Röttgers from the University of Bonn illuminates the group’s evolution in his Bachelor’s thesis

With its catchy melodies and opulent stage shows, British rock band “Genesis” (‘No Son Of Mine’, ‘I Can’t Dance’) went down in the history of contemporary music. Even now, many fans believe that in some sense there were two iterations of the group – under its lead singers Peter Gabriel (1967-75) and Phil Collins (1976-96), it was thought to have developed completely different musical styles. In his Bachelor’s thesis “Two eras of Genesis?” English major Philipp Röttgers from the University of Bonn comes to a different conclusion: the often-cited “break” in the band’s artistic work does not actually exist. His study has now been published by Marburg’s Tectum Verlag.

Anyone who turns on the radio anywhere in the world will hear their pieces – for decades, British rock band “Genesis” has helped shape contemporary music. The original five musicians, later three, put out 15 studio albums with 201 songs, and have sold about 140 million albums worldwide to date. Their work features impressive, opulent stage shows and catchy melodies, for instance in “The Brazilian” (a hypnotic instrumental piece full of rhythmic experiments, percussion effects and unusual half-tone steps) and in “Driving the Last Spike,” a ten-minute ballad about the suffering of 19th-century railroad workers. In his Bachelor’s thesis, “Two eras of Genesis?” English major Philipp Röttgers from the University of Bonn studied the history of the band. He does away with the common view that there were “two versions” of the group, first a “progressive” version and then a “commercial” one.

The first frontman of the band, which was founded in 1967, was singer Peter Gabriel. Under his aegis, the group became one of the leading forces of “progressive rock” in the early 1970s. But then Gabriel left the band in 1975, and drummer Phil Collins took over his spot as lead singer. “Since then, fans have been divided into two camps,” reports Philipp Röttgers. The first, he says, celebrates the “progressive” pieces of the Gabriel era and claims that the group only made “cheap pop” later on. The other camp says, “the music was much catchier under Collins than the weird stuff that came before.” This dispute is especially apparent in fan forums – sometimes with a fairly harsh exchange of words.

Did the band’s alleged change really happen?

Philipp Röttgers, born in 1989, does not belong to either camp. “I am a fan of all of it. ‘Genesis’ has been my favorite band since I was a child.” His study grew out of a seminar paper on “Britain in the 60’s and 70’s” with Professor Marion Gymnich, in the Department of English American and Celtic Studies at the University of Bonn. For his Bachelor’s thesis in “English Studies” – also with Prof. Gymnich – he expanded the study to about 70 pages, in fact more than 100 for the book version. “I wanted to investigate whether this alleged ‘transformation’ really took place,” says the English major in describing his approach. To do so, he compared songs and stage performances from both phases of the band’s history; his analysis also looked at reviews of Genesis songs and performances in the trade press and by fans; record and CD covers; and music videos.

“The change in singers did not make a big difference,” Röttgers sums up. As before, he says, there were still long, epic songs. As before, the visual aspect remained important: Peter Gabriel used costumes, and Phil Collins used clever music videos. As before, new pieces also grew out of the musicians’ jam sessions. Even the difference between the two key figures was “not as great as people assume,” says Röttgers. It is almost easier, he says, to find commonalities. “At least at the time, they had fairly similar voices. There’s the way that they write their music: turn the rhythm machine on, sit down at the keyboard, sing along. Funnily enough, today they even look quite similar.” In addition, the role of the other two band members – guitar player Mike Rutherford (also known for “Mike and the Mechanics”) and keyboard player Tony Banks – should not be overlooked. Röttgers finds the accusation that Genesis was “packaged in a poppier way” after 1975 to be unfair. “In the eighties, music just sounded like that. Even Peter Gabriel – look at ‘Sledgehammer’ from 1986, one of his most successful solo pieces. If Peter Gabriel had stayed, that could have been a Genesis piece, too.”

The paradox in the fan scene

Röttgers criticizes a paradox within the progressive scene: “to progress” means to advance – and yet bands are expected never to change once they have found their style.” Röttgers sees this quite differently. Of all the “progressive” bands, he says, Genesis was still the most progressive, while some other bands’ albums really are interchangeable. “Genesis, by contrast, always did their own thing, and were not influenced by the press or their fans.”

Publication: Röttgers, Philipp: Two eras of Genesis? The development of a rock band. Tectum-Verlag, Marburg (Lahn) 2015, 120 pages, 24.95 euros

Interview Leland Sklar & Daryl Stuermer (2019)

In June 2019 I had the opportunity to interview two of Phil Collins’s longest serving band members: bassist Leland Sklar (of Phil Collins, Judith Owen, James Taylor, Toto or Jackson Browne) and Phil Collins and Genesis guitarist Daryl Stuermer.

We talked about their career, touring life, Mike + The Mechanics Official as support act, how music making has changed since the beginning of their careers and where they wouldn’t play at all.

Music journalism

„Journalism is a low trade and a habit worse than heroin, a strange seedy world of misfits and drunkards and failures.“ (Hunter S. Thompson.)

I write for several music magazines such as Intro, Festivalguide, BetreutesProggen, The Dutch Progressive Rock Page, Reflections of Darkness and more. I also occasionally write book reviews for Booknerds.

8 thoughts on “Two eras of Genesis? The development of a rock band (2015)”